A brief overview:

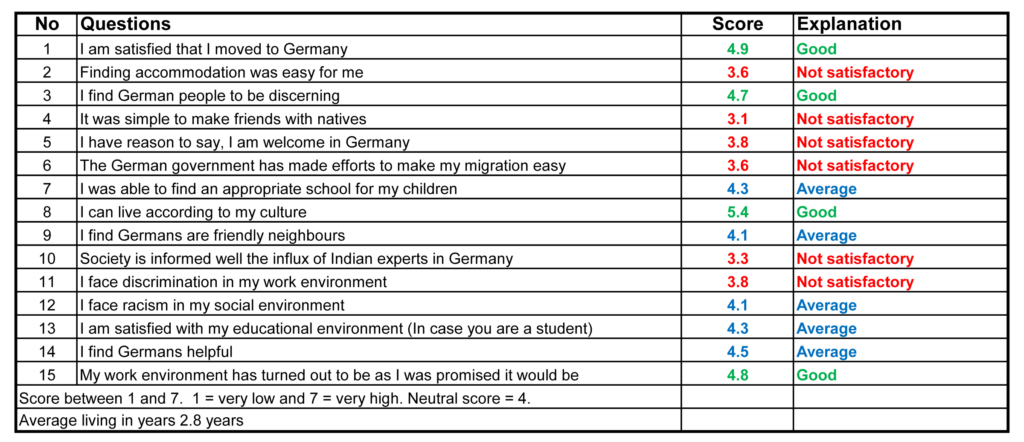

The Ezenz e.V. administered a 15-question quantitative and randomised survey in October 2023. To gauge the degree of contentment among Indian professionals who had moved to Germany, participants were requested to rank their answers on a scale ranging from 1 to 7. A period of no more than three years spent living in Germany. The reasoning behind this is that migrants during this period have not completely assimilated into the host culture, adjusted their expectations, or rejected any aspects of it. As far as our goal was concerned, this was a plus. The outcomes are presented at the article’s conclusion. Three out of 15 questions had ratings between 4.7 and 4.9, and one question (out of fifteen) got a grade of 5.4. The scores on the other eleven questions were mediocre to poor, falling on a scale from 3.1 to 4.5. Now, we will examine two instances:

The first question, “I am satisfied that I moved to Germany,” received a score of 4.9 out of 7, or 70%. Even a more encouraging 80% would be considered a stretch for this.

Question 4, “It was simple to make friends with natives,” Received a failing grade of 3.1 out of 7, or 44.28%.

Indian professionals are not “Gastarbeiter”.

An abundance of articles, including one by InterNations with the headline “expats in Germany are among the unhappiest worldwide,” have noted the difficulty of making friends in Germany. Their happiness score is 64%, lower than the global average of 72%. “Berlin and Hamburg expats are among the unhappiest worldwide” (Oliver Logan, 16 November 2023) is the subject of an additional article. The score is a reflection of society’s evolution; some may be quick to blame Germany, but I don’t see anything wrong with it. Societies do not evolve in response to external wishes, therefore, expecting the locals to change their behaviour contrary to their culture for the sake of migration is an unrealistic expectation. The reality must be faced, and we may consider adjusting to it to devise a method of dealing with it. The idea that those who have freely relocated to Germany in search of a better life will not discover a social paradise is the foundation of this acceptance.

The first time I came in 1979, things were difficult, to say the least. I opted to remain here because the benefits outweighed the drawbacks back home. There was a clear disapproval and a magnanimous attitude towards the foreigners, who were referred to as Ausländer and were viewed as inferior. People of foreign appearance were stereotyped as “Gastarbeiter,” or low-wage workers who had flooded into Germany following WWII as a result of the country’s government’s initiative to address the severe lack of male workers. It was widely believed that Germany was helping them out. In reality, nobody tried to include them or take their needs into account during any thoughtful debates. The 1,000,000th person to arrive in 1964 was welcomed with a moped. Many men left their families behind to become “Gastarbeiter” laboured tirelessly and helped develop this nation. Later on, they brought their family in and tried to blend in with society as little as possible. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that locals started to wonder what exactly a “Gastarbeiter” was. They were originally scheduled to be temporary employees, but they remained. Integration and assisting newcomers in teaching their native language were not considered at all. They were the punchline to utterly stupid jokes for the better part of a decade. In the early 1990s, the German media began covering an IT expert phenomenon as if it were a wonder, something no one had expected. The true explanation lay in the fact that the German media ignored the transformation the Indian educational system had undergone. In 2000, Mr. Juergen Ruettgers of the CDU political party had the best reaction he could muster to this shortcoming: “Kinder statt Inder.” Except for being late, his rationale was sound. In his place, he suggested sending the kids to school for computer training instead of relying on Indian experts. Instead of doing its job and keeping the people informed about global events, the German media frequently indulges in sensationalizing stories. It is possible that some Germans would have responded sooner if the media had fulfilled its duty and educated the public about the developments in India’s IT sector from the 1980s. Even after 23 years, the economy is still struggling to get Inder, and Mr. Ruettgers’s answer to Kinder seems to have fallen short of its illusions too. The demographic decline induced by modern lifestyle choices is the root cause of the human resource shortage. Some parts of this issue are discussed extensively in Professor Andreas Reckwitz’s book Die Gesellschaft der Singularitaeten. The shortage on many fronts is not limited to blue-collar or white-collar jobs; even the most qualified candidates must be enticed.

The most important question.

Considering the gravity of the situation, lawmakers have revised immigration regulations. Is the public aware and ready for the arrival of newcomers? That is the most important question. Does this nation have a welcoming culture that makes professionals want to come to Germany, or does it continue to look down on them as individuals from the third world and treat them the same way as refugees and economic fugitives? “Was haben wir denn zu bieten denen?” The president of the employers’ association, Mr. Rainer Dulger, asked, on the ARD television channel on November 26, 2023. What do we offer them? Getting them to carry out their Gastarbeiter duties on a moped quietly is not going to cut it. The chance to learn from our errors and provide accurate information to the public is presented by Mr. Dulger’s query. It is time for the media to stop sitting on their hands and start actively assisting the country in reaching its objectives; otherwise, the consequences of inaction will catch them unawares once again. How might the media intervene?

A wise person can go to a quote from philosopher Avishai Margalit’s book, A Descent Society, for direction. “…that there is a weighty asymmetry between eradicating evil and promoting good. It is much more urgent to remove the painful evils than to create enjoyable benefits. Humiliation is a painful evil, while respect is a benefit. Therefore, eliminating humiliation should be given priority over paying respect.” He is also inspired by Carl Popper’s book, The Open Society, and Its Enemies in his thoughts. The public media is causing Margalit’s evil, and unless it is eliminated, Germany will struggle to hold on to or recruit professionals. Either it chooses to stay silent, or it spreads biased and false reports. About a hundred young Indian professionals approached me between 2019 and 2023 for various reasons; among them was the belief that the German media treats India with disdain and humiliates them. The fact that the Indian parents felt their children’s textbooks portrayed India as though Germany was stuck in the 18th century was another point of contention. Indian experts are desperately needed by the German economy, but the people must be made aware beforehand that they are not Gastarbeiter. The locals could feel more heard and valued if they had conversations and interviews with these experts about their issues. As far as I can tell, in 2015, the locals have always been quite generous and helpful whenever asked to help during a crisis. The nation’s leaders and news outlets appear oblivious to this boon.

Disgrace or Deference?

Indians take offence at the slightest hint of colonial intimidation or attitude. This is a common pattern in the German media. Deutsche Welle tweeted a photo dated 01.12.2023 of a fanatic who threatened to bomb an Air India flight in November 2023 and assault the foundations of Indian democracy on December 13, 2023. According to the DW, he is an activist. Many in the Indian diaspora find this offensive and humiliating.

Even though he was a militant Islamist, news outlets portrayed Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh as a liberation fighter up to February 1, 2022. The United States and the European Union stood idly by as he and his ilk assaulted India. It was only after the innocent Wall Street journalist Daniel Pearl’s decapitation; that the same news outlets rebranded him as a terrorist. Indians are quite sensitive to this indifference to their suffering; as a result, they prefer to avoid discussing the plight of the Ukrainians, even though they disagree with the war and sympathize with their suffering.

The solution.

The solution is to get them closer by not acting as if terrorist threats to India are your activists or it is some freedom of speech. If I were to interpret the thoughts of Margalit, this negligent and deliberate trivialization is a painful humiliation and an evil. There is an urgent need to abolish these evils if you want to offer an answer to Mr. Dulger; what do we offer them?

Arun Kohli

Munich, Germany